Program

Music by William Byrd — Written and Directed by Bill Barclay — Co-Produced by Concert Theatre Works & The San Francisco Early Music Society — Featuring The Gesualdo Six and Wildcat Viols

Prelude

Three Fantasias in 3 parts

Fantasy a 5: Browning, or The Leaves be Green

Main Performance

Memento, homo

In Nomine a 5

Mass for 5 Voices: I. Kyrie & II. Gloria

Fantasia a 6 No. 2

Mass for 5 Voices: III. Credo

Fantasia a 6 No. 3

Mass for 5 Voices: IV. Sanctus, V. Benedictus & VI. Agnus Dei

Interruption

Elegy on the death of Thomas Tallis (Ye Sacred Muses)

Agnus Dei (from the Mass for 4 Voices)

“Communion”

Pavan & Galliard a 6

Infelix ego (a 6)

Haec Dies

Concert Theatre Works

Concert Theatre Works is a creative production company that fuses storytelling with live classical music to craft unique performances. Operating between the US and UK, it aims to engage new audiences through theatrical spectacle. Led by composer and director Bill Barclay, the company collaborates with renowned ensembles, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Its productions, showcased in prestigious venues like The Kennedy Center and Buckingham Palace, utilize diverse elements, including actors, projections, and sound, to deliver dynamic interpretations of music while highlighting marginalized narratives, thereby asserting the importance of the performing arts as a political act.

About the director

Hailed a “personable polymath” in The London Times, Bill Barclay is Artistic Director of both Concert Theatre Works and Music Before 1800, New York’s oldest early music presenter. He was Director of Music at Shakespeare’s Globe from 2012- 2019, producing music for over 120 productions and 150 concerts. He composed the original score for 12 Globe productions, including Hamlet Globe-to-Globe, which toured to 197 countries. He was Music Supervisor on Broadway and the West End for Farinelli and the King, Twelfth Night, and Richard III, all starring Mark Rylance and performed on period instruments.

A passionate advocate for evolving the concert hall, Barclay has created over 20 works of concert-theatre for the world’s leading ensembles, including the LA Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican, and six commissions for The Boston Symphony Orchestra including The Chevalier, Peer Gynt, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Magic Flute, and L’Histoire du Soldat. Other collaborators include Silkroad, The Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Center, National Symphony Orchestra, City of London Sinfonia, National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain, Washington National Cathedral, Tanglewood and Spoleto Festivals, and Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Virginia, Winston-Salem, and Buffalo Symphonies. He has collaborated with a number of historically informed ensembles, including The English Concert, The Sixteen, Music of the Baroque, and Barokksolistene. He returns to St Martin in the Fields this March with the London Philharmonic Orchestra for the UK premiere of The Chevalier.

Barclay seeks to collapse the space between arts and advocacy, composing the film A Mother’s Love for the Wild Foundation, creating Tales in Migration to score immigrants’ stories, and funding The Sphinx Organization’s National Alliance for Audition Support. His single “Let Nature Sing”, made entirely of birdsong with folk singer Sam Lee, debuted at #11 on the UK Pop Charts for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Secret Byrd addresses the fresh threat today of belief intolerance around the globe.

A noted curator, he piloted the Candlelit Concerts series in the Globe’s Sam Wanamaker Playhouse from its construction in 2014, featuring major collaborations including the Royal Opera House, BBC Proms and London Jazz Festival, and with guest curators John Williams, Trevor Pinnock, Lauren Laverne, the Brodsky Quartet, and Anoushka Shankar.

Barclay’s original music has been performed for President Obama, the British Royal Family, for the Olympic Torch, at the United Nations, in Buckingham Palace, and in refugee camps in Jordan and Calais. He is the founder of the label Globe Music, recognized by the BBC, The Royal Philharmonic Society, and Songlines (Top of the World, 2016), with releases featuring Ian Bostridge and Soumik Datta. He recently created a new Four Seasons Recomposed for Max Richter on period instruments with the puppetry masters Gyre & Gimble.

The Gesualdo Six

“Ingeniously programmed and impeccably delivered, with that undefinable excitement that comes from a group of musicians working absolutely as one.” – Gramophone (2020)

The Gesualdo Six is an award-winning British vocal ensemble comprising some of the UK’s finest consort singers, directed by Owain Park. Praised for their imaginative programming and impeccable blend, the group formed in 2014 for a performance of Gesualdo’s Tenebrae Responsories in Cambridge and has gone on to perform at numerous major festivals around the world.

Notable highlights include a concert in the distinguished Deutschlandradio Debut Series, performances at renowned venues including Wigmore Hall (London), Miller Theatre (New York), the Sydney Opera House, and their debut at the BBC Proms in 2023. In 2024, The Gesualdo Six made their South American debut in Colombia, and will appear in Japan, China and Singapore for the first time. The ensemble have collaborated with Fretwork, the Brodsky Quartet, and Matilda Lloyd, and tour a work of concert-theatre titled Secret Byrd with Director, Bill Barclay.

The Gesualdo Six is committed to music education, regularly hosting workshops for young musicians and composers. The ensemble have curated two Composition Competitions, with the most recent edition drawing entries from over three hundred composers worldwide. The group recently commissioned new works from Shruthi Rajasekar and Joanna Marsh, alongside coronasolfège for 6 by Héloïse Werner.

The ensemble have harnessed the power of social media to make classical music accessible to millions worldwide, creating captivating videos from beautiful locations while on tour. The group released their debut recording English Motets on Hyperion Records in early 2018 to critical acclaim, followed by seven further albums (Christmas, Fading, Josquin’s Legacy, Gesualdo’s Tenebrae Responsories, Lux Aeterna, William Byrd’s Mass for five voices, & Morning Star) and most recently Queen of Hearts.

Wildcat Viols

Wildcat Viols was formed in 2003, bringing together three of the San Francisco Bay Area's favorite early string specialists, Joanna Blendulf, Julie Jeffrey, and Elisabeth Reed, and was joined in 2015 by internationally recognized viol virtuosa Annalisa Pappano. Praised for their musical rapport and the shared enjoyment that radiates from their performances, they have been hailed as "refreshing", "sensuous", "gutsy", "incredible artists", "breathtaking ensemble." Early Music America magazine called their debut concert at the 2004 Berkeley Early Music Festival a "wonderful offering . . . beautifully played." In 2010 Wildcat Viols, at the invitation of Artistic Director George Benjamin, performed the complete 3- and 4-part Fantazias of Henry Purcell at the Ojai Music Festival, receiving lavish audience and critical praise: “Articulated fluently . . . with impeccable intonation” (The Classical Review); “The expert period instrument group produces a focused ensemble sound . . . and delivered the music in all its intricately designed, soothing glory" (Santa Barbara News Press); “A balm . . . endlessly absorbing” (The London Financial Times); “Spellbinding . . . fantastic." (WQXR, the Classical Music Station of NYC). Wildcat Viols’ recording of the complete four-part Fantazias of Henry Purcell, the complete viol sonatas of Giovanni Legrenzi and selected Consorts of Four Parts by Matthew Locke (released in 2018) has been enthusiastically received: “This is an outstanding disc, the playing responsive and expressive at all times… a recording crying out to be eagerly revisited… It would be good to hear more from this exciting ensemble.” (The Viol, British Viola da Gamba Society); “The sound they make… is not just incredibly powerful, it’s beautifully blended, truly concerted, like the best chamber music… top-flight musicmaking.” (San Francisco Classical Voice).

Wildcat is joined by two guest artists for this performance, David Morris and Farley Pearce.

MEMENTO HOMO QUIA PULVIS ES ET IN PULVERE REVERTERIS:

Recusant Worship in Reformation-Era England

By Beatrice Dalov

“The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; those who dwelt in a land of deep darkness, on them has light shined. ”

In hushed tones set to flickering candlelight, recusant Catholics recite the illicit liturgy of the Mass, assemble impromptu consorts of singers and instrumentalists, and consecrate bread and wine in an intimate performance of the Last Supper. Their chapels—some even equipped with organs—nestle behind false walls, above hidden attics, and in inconspicuous country homes away from the purview of royal spies; yet, notwithstanding its elaborate ritual and array of relics, their worship is ephemeral, easily transfigured into an innocuous, even unmemorable, gathering if discovered or expropriated. Crucifixes, chalices, patens, and hymnals adorn immaculate altar cloths yet lay within short reach of ingenuously concealed “priest holes,” inside which both preacher and paraphernalia could cower in the event of a search. Catholic worship in sixteenth-century Reformation England was precarious in its willful admission to political treason—indeed, it embodied the visceral pursuit of a capriciously persecuted peoples for a pious, and indeed zealously messianic, communion with the divine.

“Catholic worship in sixteenth-century Reformation England was precarious in its willful admission to political treason—indeed, it embodied the visceral pursuit of a capriciously persecuted peoples for a pious, and indeed zealously messianic, communion with the divine.”

Laying the ideological groundwork for the Protestant Reformation were Renaissance humanists who called for a return ad fontes of Christian faith— the Scriptures as understood through textual and linguistic scholarship—and maintained that Catholic pillars of justification, such as the Mass, the sacraments, charitable acts, prayers to saints, pilgrimages, and the veneration of relics, represented mere superstition at best and idolatry at worst. Yet the Reformation as it unfolded in England radically differed in ambition from its parallels on the Continent—rather than a populist insurgency led by a small sect of fervent clerics, the Isles embraced Protestantism primarily in response to Henry VIII’s (1491–1547) personal inconveniences with Pope Clement VII’s denial of a marriage annulment in 1527, and secondarily from a centuries-long contest for power between British monarchs and the Catholic Church. Although Protestants and Catholics devoutly embroiled themselves in fundamental questions of doctrinal legitimacy, the English Crown concerned itself less with theological cavils than with an ongoing consolidation of secular and ecclesiastical hegemony against the Roman papacy, fiercely conflating religious allegiance with political loyalty. England’s Reformation, more than a quibble over religious difference, was a profoundly political revolution—in federating the increasingly authoritarian Crown’s power over the kingdom, Henry vied to channel public loyalty toward himself, rather than the Holy See.

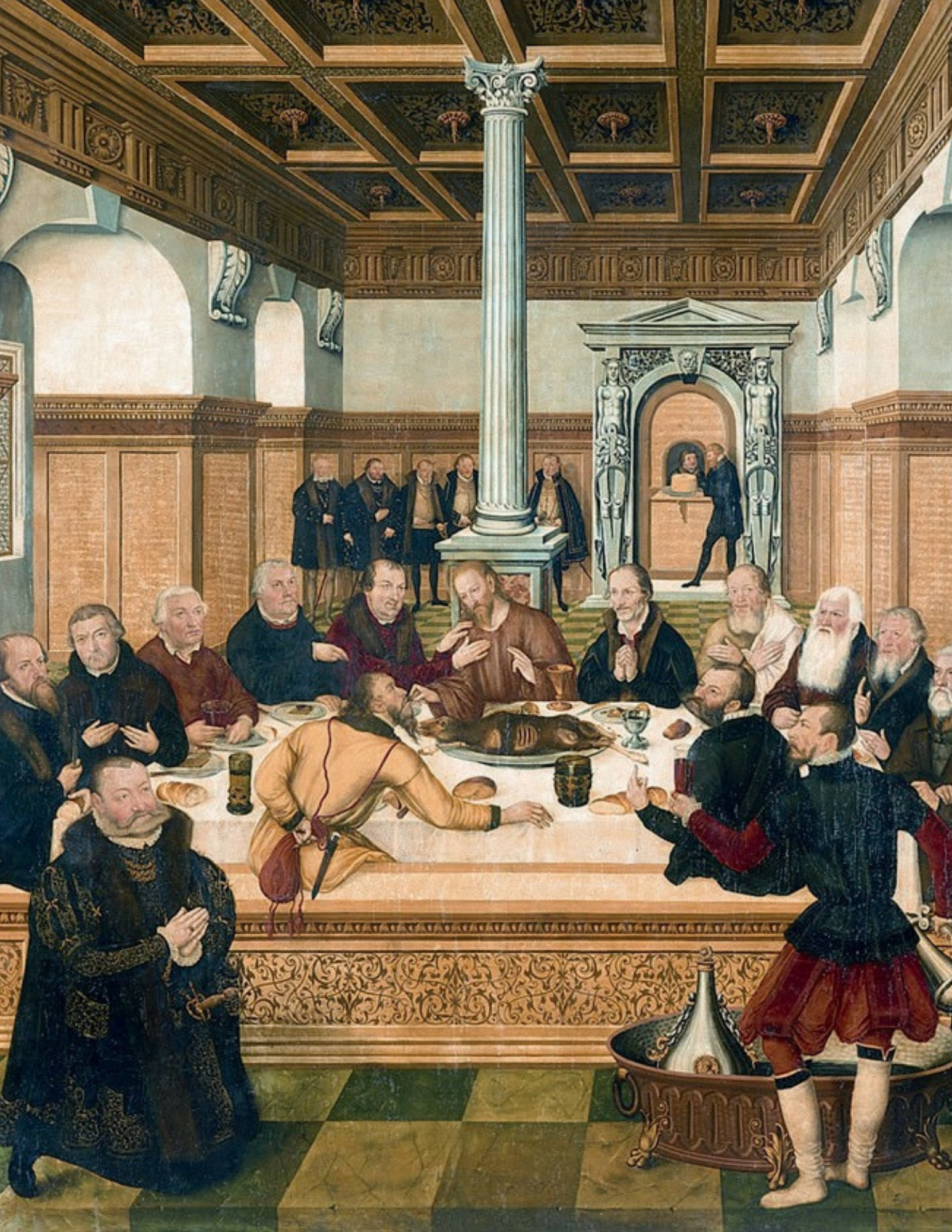

Last supper (1565), oil on panel, Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515–1586). In contrast to catholic churches, protestants often selected depictions of the Last Supper as altarpieces, reflecting their affirmation of Christ’s pneumatic presence during communion. In this untraditional rendering of the Last Supper, Cranach portrays leading protestant reformers as the apostles—Luther is in the left-hand corner, the German theologian philip melanchthon sits on the right of Christ, and the Elector of Saxony kneels at the front of the composition.

Shrouded by the commotion of his romantic and political floundering between Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, the insouciant monarch led the country to papal excommunication and—by means of the Reformation Parliament of 1532–1534—declared himself the “one Supreme Head and King” of England. Thus the notion of treason morphed into a profoundly dangerous ideology, signifying not merely an act against Henry VIII, inwhom both governmental and divine authority were intimately wedded, but also against God; by natural extension did the sacraments through which the faithful received celestial grace—Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, Holy Orders, Anointing of the Sick, Penance, and the Eucharist—likewise transform into declarations of sedition against the Crown when performed in communion with Rome, rather than under he sanctions of the Church of England. Yet such abrupt, and indeed opportunistic, deposition of the Catholic Church hierarchy polarized England and, therefore, sustained itself foremost through violent measures. Henry VIII, a religious traditionalist by conviction, relied on Protestants—his most important supporters in breaking with Rome—to implement and enforce a religious agenda that advanced his personal and political ambitions, albeit occasionally at the expense of his own persuasions. Thus the sounds of the English Reformation enveloped the sharp knocks of spies on unsuspecting doors; the toppling of statues in town centers that, contextually, morphed into displays of heresy; the forcible dissolution of monasteries loyal to Rome, in which the wealth of the Catholic Church was concentrated; and the echoes of stinging words of conflict over prayers, rubrics, and musical sensibilities within the country’s once-grandiose cathedrals—what they instigated, however, was a period of doctrinal confusion as both conservatives and reformers battled to dictate the Church of England’s identity.

The Glorification of the Eucharist. (ca. 1630–1632), oil on wood, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). the metropolitan museum of art.

Emphasizing movement, color, and sensuality in a style distinct to the catholic counter-reformation, Rubens depicted the risen christ triumphing over sin and death (represented by the snake and skeleton, respectively) and flanked by Melchizedek, Elijah, Saint Paul, and Saint Cyril of Alexandria, who were all associated with the eucharist.

If Henry VIII did little to reform the country in theological terms, then the six-year reign of his son, Edward VI (1537–1553), dramatically repositioned Anglicanism as in concert with Protestantism, a shift in large measure stewarded by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556), who professed strong objections to the Catholic liturgy—indeed, it was through him that sweeping search-and-destroy missions came into common practice, effacing much of early English polyphony and advocating for a “plain and distinct” musical style to proclaim the Dei verbum. With the 1553 ascension of Mary I (1516–1558), or “Bloody Mary,” to the throne, however, the pendulum once again swung in Catholicism’s favor—undoing many of Edward’s Anglican reforms, she burnt Cranmer at the stake, promulgated Protestantism as an illegal heresy, and—by the time of her death in 1558—brought the country to the brink of a religious civil war.

Etching of William Byrd (ca. 1730–1770), etching on paper, Gerard van der Gucht (1696–1776) after Nicola Francesco Haym (1679–1729), The British Museum.

Perhaps the last relevant monarch in the context of the English Reformation in general and William Byrd’s (ca. 1540–1623) musical career in particular, Elizabeth I (1533–1603) inherited from her half-sister a theologically divided kingdom whose primary ally was Catholic Spain—a holdover from Mary’s marriage to King Phillip—yet in which most subjects, especially the political elite, were religiously conservative. Thus, her Elizabethan Settlement, implemented between 1559 and 1563 and broadly marking the conclusion of the English Reformation, reestablished the Church of England’s independence from Rome yet gave greater latitude to its liturgical structure in an attempt to reconcile—or at least assuage—the latent political tensions between Catholics and Protestants. Her preponderance for elaborate rituals within the Church of England allowed for Latin polyphony to experience a rebirth, and she did not seek to subject recusants to legal reprisal.

Yet, resentments continued to fester, and—following Pope Pius V’s 1570 papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which effectively absolved Elizabeth’s Catholic subjects from their allegiance to her, compounded by the enduring threat of invasion from France or Spain—Catholicism increasingly became synonymous with treason in the perception of Tudor authorities. Likewise, rising suspicions that Elizabeth allowed too many concessions to Catholics galvanized Protestants to ravage her private chapel on several occasions over the 1560s, in which her collection of crucifixes, candlesticks, and religious artifacts with Latin inscriptions foisted assumptions of religious dissent upon the monarch herself. Thus, in a corrective political move, Elizabeth flooded her government with Protestants and began a generally impassioned persecution of Catholics as religious heretics and treasonous subjects, freely leveraging royally dispatched spies, trials, and executions to build a climate of fear in the absence of a standing militia or police force.

Byrd came to maturity in this politically tenuous and doctrinally schismatic environment and indeed represented “the end of the line” in English Catholic music, bringing to a climax a tradition on the losing side of the Isles’ theological war. By the time Byrd entered into his first known professional employment in 1563 as organist and master of the choristers at Lincoln Cathedral, three Protestant variations about the nature of music in church pervaded English society, unified primarily by their agreement that the “obscurantist” traditions of the late medieval church needed replacement: moderates shared Martin Luther’s opinion that music was a vital tool of persuasion; stronger-minded reformists developed, in the vein of Calvinists, a suspicious acceptance of it; and the most radical denied the validity of virtually all music in public worship, fearful that it made congregants vulnerable to carnal pleasures. Byrd, who exhibited no strong qualms about composing for Anglicans, nonetheless succumbed early to the attractions of luxuriant Catholic music and readily encountered resistance from clerical authorities.

Portrait of Martin Luther (1483–1546), oil on wood, workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Well-acquainted with Martin Luther and heavily involved in the production of images for the Protestant Reformation, Cranach created illustrations for the Bible and for Luther’s sermons, lectures, polemical tracts, and broadsheets.

On November 19, 1569, the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral cited him for “certain matters alleged against him,” among which his proclivity for elaborate choral polyphony and florid, virtuosic organ playing almost certainly numbered. Indeed, Byrd firmly positioned himself against the excessively simplified chant, espoused in Cranmer’s 1552 Book of Common Prayer, that was functional, comprehensible to, and accessible for the average worshipper, preferring instead the overtly expressive and sophisticated polyphony that epitomized the Catholic tradition; yet in adopting such a style, he precariously blasphemed the Protestant leanings of both church and state.

In the early 1570s, however, Byrd assumed a coveted post as Gentleman in Her Majesty’s Chapel Royal, forging the first of several critical links to the royal court and finding protection from anything but cursory reprimands of his thinly veiled predispositions. Elizabeth, a moderate Protestant with musical inclinations, valued Byrd both as an organ virtuoso and highly adept composer who brought a weight of distinction in the eyes of visiting dignitaries, and as a relatively tempered Catholic who acted as a bargaining chip in Elizabeth’s negotiation of her religious reputation abroad.

The Denial of Saint Peter (1610), oil on canvas, Caravaggio (1571–1610). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Caravaggio, employing a dark and expressive style largely without precedent in European visual art, focused on Peter’s poignant repentance following his denial of Christ in keeping with Counter-Reformation theology.

Insofar as Byrd offered gestures of conformity—such as his 1575 Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur, rife with patriotic rhetoric dedicated to “Her Most Serene Majesty the Queen” and printed under a joint Letter Patent with Thomas Tallis (1505–1585), his Chapel Royal colleague—Elizabeth ceded that he could style himself as both a privately stiff papist and a publicly loyal subject. Indeed, court and composer maintained a resilient relationship—despotisms have both arbitrary victims and beneficiaries.

Yet Elizabeth’s reign was profoundly turbulent, racked by a papal bull that released English Catholics from their presumption of loyalty, the unsuccessful Revolt of the Northern Earls, an attempted invasion from Spain, a series of underground plots to assassinate and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots, and the fomentations of the Counter-Reformation Society of Jesus, which ordained priests on the Continent and missioned them to proselytize England back to Catholicism. Executions of Catholic priests, in turn, became more common: the first in 1577, four in 1581, eleven in 1582, two in 1583, six in 1584, fifty-three by 1590, and seventy more between 1601 and 1608 stoked fear of a larger insurrection against the Crown.

Necessarily resulting was a monarchy steeped in paranoia, where allegiances and loyalties were subject to constant checks and suspicions—thus Byrd, whose private life increasingly gave itself over to the prying eyes of the overwhelmingly Protestant court, withdrew into the closet world of recusancy. By the early 1580s, following a move to the Middlesex countryside, Byrd had found company in dangerous quarters. Cramped in his ability to entertain the role of official church composer in the ars perfecta style—the range of suitable texts for motets, stringently circumscribed by the narrow limits of the Catholic-Anglican overlap, mostly consisted of psalms—he instead pivoted to a musically recusant embrace of Catholicism, appropriating the final words of his embattled coreligionists (so-called “gallows texts,” such as Infelix ego and Haec dies) into affective personal, rather than institutional, professions of a martyred faith. His frequent attendance at worship services ministered by Jesuit priests led, in 1582, to his association with Sir Thomas Paget, a known Catholic who was embroiled in the Babington and Throckmorton Plots, and resulted in his suspension from the Chapel Royal, a formal restriction on his movements, and a citation of his house on a local search list.

The Descent from the Cross (1612–1614), oil on panel, by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). Catholic churches often commissioned crucifixion scenes for their altarpieces to impress upon their congregants that the sacrifice of Christ and the sacrifice of the Mass were synonymous, realized through the literal transformation of the Eucharist.

Blithely unconcerned, he published two volumes of Cantiones sacrae in 1589 and 1591, eschewing sanctioned liturgical texts in favor of biblical pastiches that groan with the anguish of Catholicism’s persecution, exile, and alienation in a country gripped by the throes of political theology—indeed, he wove elaborate analogies that, although typically Biblical and therefore blameless in some sense, encoded the captivity of the English Catholic community into metaphors of Jewish, Babylonian, and Egyptian historical plights for religious freedom. Yet simultaneously, Byrd set to music Elizabeth’s anthem “Look and bow down thine ear, O Lord,” written in celebration of England’s victory against the 1588 Spanish Armada—thus, in the moral conflict of musical conviction juxtaposed against political protection, he painted a portrait of an apparently self-contradicting figure who was both highly sympathetic to Catholic missionaries and a supporter of the Jesuits, yet also a thoroughly loyal Englishman who performed the gestures and public statements that reinforced loyalty and obedience to the Queen.

Moving once more to Stondon Massey, a recusant community in the countryside, Byrd effectively retired from the Chapel Royal (though he remained on their formal register of members) and closely wedded himself to his patron and acquaintance since at least 1581, John Petre, for whom he began to write music to accompany clandestine Mass celebrations.

While Petre’s Catholic services attracted on occasion the unwelcome attention of spies and paid informers working for the Crown, his family was well- connected to the monarchy—Elizabeth had knighted him in 1576, and she not infrequently noted “Sir John” in her domestic papers—and he likewise held a number of government posts in Essex that favorably positioned him to brandish authority in the conscious obfuscating of his religious attitudes, enveloping his composer into his protective sphere. Thus between 1593 and 1595, Byrd composed three settings of the Mass Ordinary for four, three, and five voices, imbuing them with strained— and often poignantly dissonant—explorations of faith, divine grace, and personal ideology against a disillusioned backdrop of political fragility, theological polemics, and an excessively simplified musical tradition. Starkly contrasting their parallels on the continent, where composers offered Masses by the dozens, Byrd’s settings of England’s seditious liturgical texts evidence a sublime awareness of, and reverence for, their semantic content; indeed, they offer a quintessentially Catholic consideration of religiosity and worship, culminating with their unified choral declamations on the confession “Et unam, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam Ecclesiam” (“Yes, I believe in one holy, catholic, and apostolic Church”). Yet he flaunts, once more, both his political caution and his brazenness: published with no title page or obvious incriminating marker on their cover, the three Masses betray Byrd’s name scrawled on every sheet of the manuscript—an audacious declaration of his faith and of the power structures that so often shielded him from its repercussions.

Noli me Tangere (1526–1528), oil on panel, Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543). Royal Collection Trust. While Protestant oil paintings of Christ from the Reformation era are relatively rare, Protestants generally distrusted the presence of religious art in churches. This depiction of Mary Magdalene’s discovery of Christ risen from the tomb embodies the direct mediation of the individual with the divine, central to Reformation ideology.

Yet in 1603, when Queen Elizabeth I passed away, Byrd did not neglect to pay homage to his royal patron—in the Chapel Royal’s books for the Gentlemen’s morning livery, his name appears, in florid lettering, under the account of her funeral service. He, likewise, would not overlook appealing to the new regime for support, writing sometime between 1605 and 1612 to the Earl of Salisbury, chief secretary to James I, to confirm the understanding he had with Elizabeth that allowed him to indulge his musical predilections for Catholicism’s ars perfecta:

“The humble petition of William Byrd, one of the gentlemen of His Majesty’s chapel, that being to crave the council’s letter to Mr. Attorney General to like effect and favour for his recusancy as the late greatest Queen and her council gave him.”

The vein of risk coursing through Byrd’s— and every Catholic’s—life in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England certainly never abated; yet it fundamentally animated both his theological and his musical expressions of faith, concentrating the visceral experiences of persecuted worship into a monumental figurehead—while also bringing into sharp relief the systems of power and privilege underlying the Reformation’s violent political ambitions.