The PDF program is not optimized for mobile view. The virtual program below provides supplemental information to the program booklet.

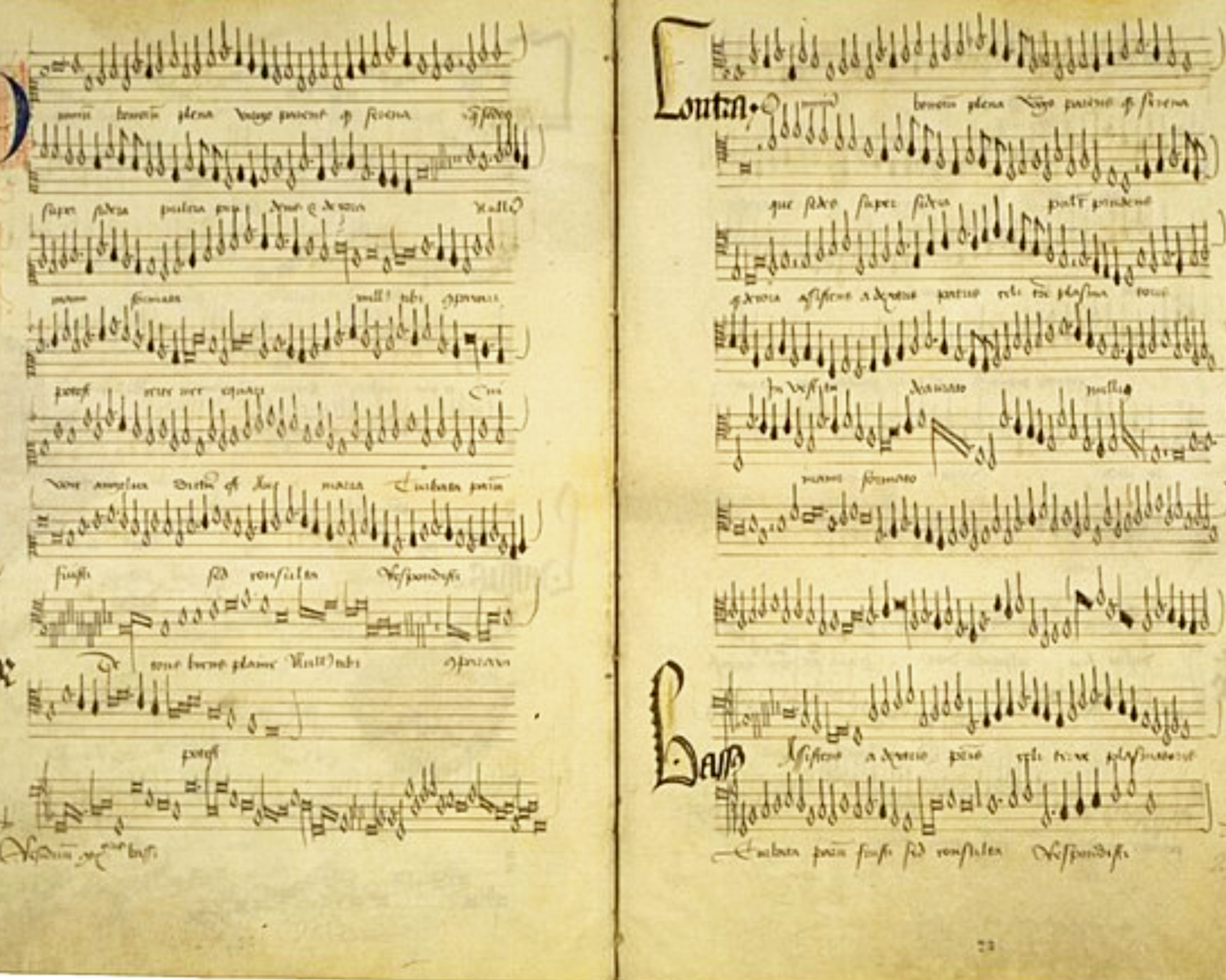

stile antico

The Old Style

“...composers continued to be trained to compose in the a cappella, ars perfecta style (or what was taken as the “Palestrina” style) for Roman church use long after Palestrina’s time. By the early seventeenth century, two styles were officially recognized by church composers: the stile moderno, or “modern style,” which kept up with the taste of the times, and and stile antico, or “old style,” sometimes called the stile da cappella, which meant the “chapel” style, which is to say the timelessly embalmed Palestrina style, a style that had in effect stepped out of history and into eternity.”

(Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music)

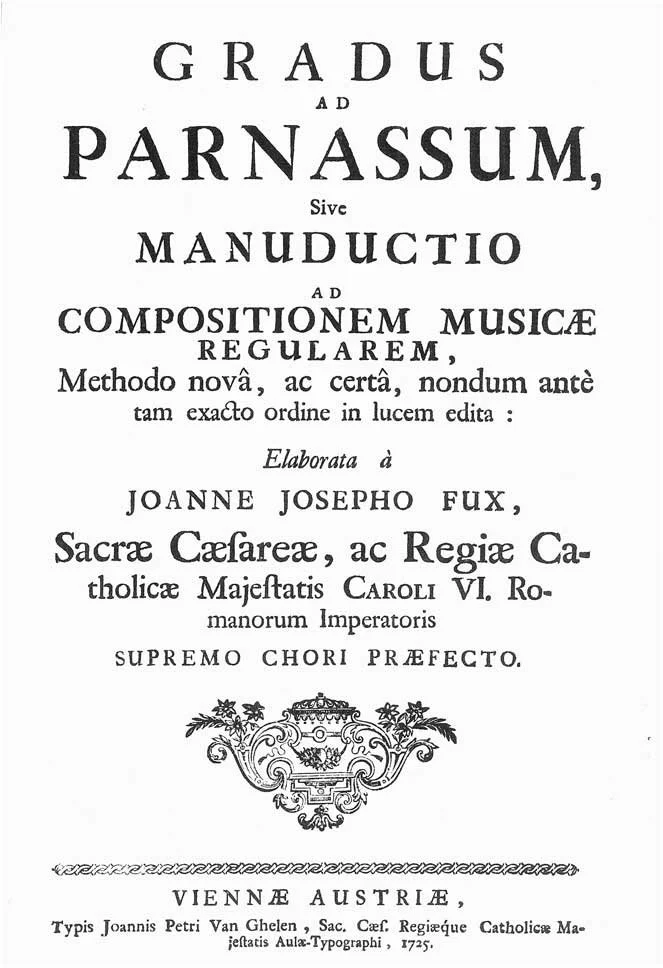

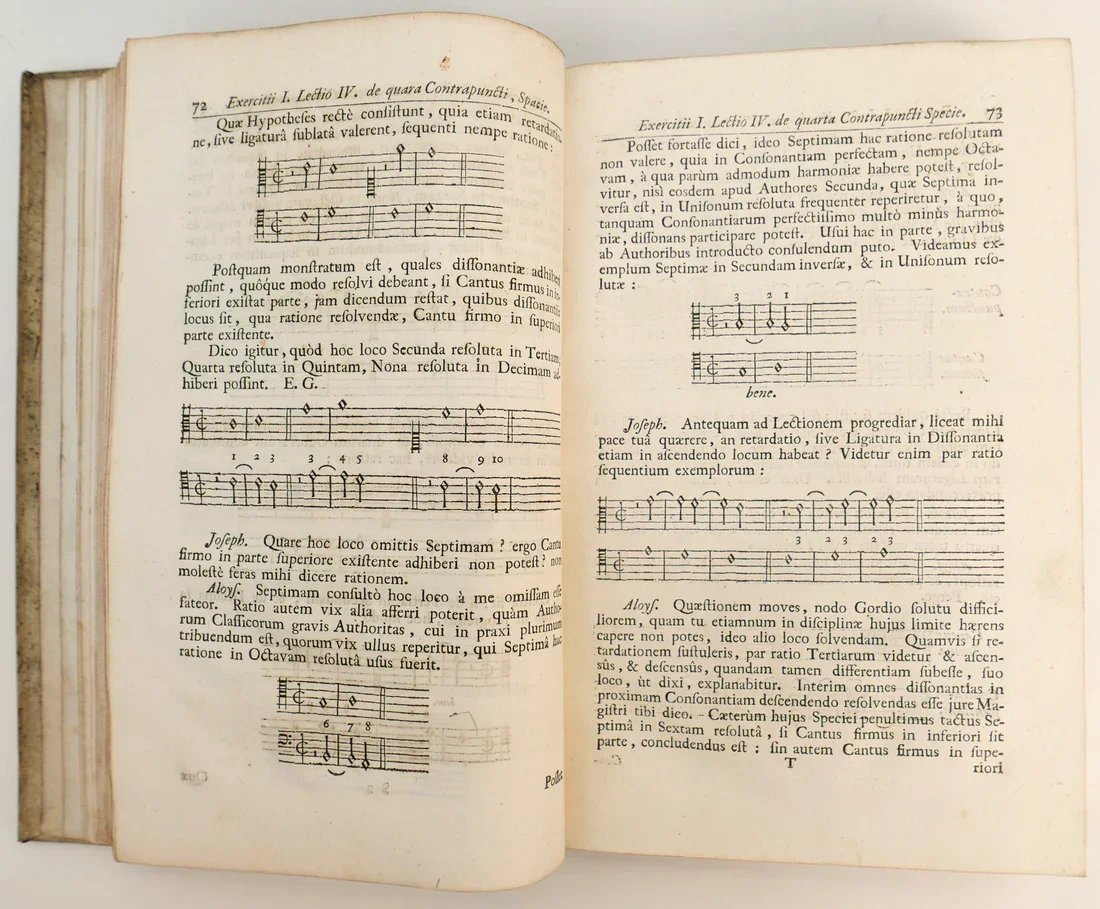

Gradus ad Parnassum

Gradus ad Parnassum (tr: “Stairway to Parnassus”) is one of the most enduring and influential texts in western music theory & composition written in 1725 (200 years after Palestrina’s birth) by Johann Joseph Fux (c. 1660–1741). ‘Gradus’ is written as a dialogue between a pupil (Josephus) and master (Aloysius) representing Palestrina.

“By Aloysius, the master, I refer to Palestrina, the celebrated light of music… to whom I owe everything that I know of this art, and whose memory I shall never cease to cherish with a feeling of deepest reverence.” (from the author’s foreword to Gradus ad Parnassum)

“Gradus” outlines a strict method of composition, through “species counterpoint” rules and exercises establishing a harmonic foundation which would influence composers for centuries to come.

An old SFEMS meme

The Pope Marcellus Mass

and the Council of Trent

Council of Trent, painting by Elia Naurizio (1589–1657)